As the era of U.S. primacy comes to an end, academics and policymakers have quite naturally been debating what comes next. Will the emergence of a multipolar world prove inherently destabilizing? Is the dominance of a single power necessary for peace and prosperity?

Increasingly, the consensus in the West seems to be that multipolarity, or the absence of hegemony, could easily lead to chaos. Yet this conclusion often relies on evidence from the recent history of the United States and Europe. Kenneth Waltz, for example, anchored his groundbreaking argument about the instability of multipolar systems by contrasting trends on the European continent before and after the start of the Cold War. Similarly, the belief that only a single dominant power can facilitate market access and security protection—what scholars building on the work of Charles Kindleberger have called hegemonic stability theory—largely relies on the experience of the United Kingdom before World War I and the United States after World War II.

But the future of the international order might be more promising when you look for precedents outside of the 20th century West. More distant history provides some dramatic examples of how multipolar systems have managed to maintain peace. The challenges the world faces today are different from those faced by the great kings and pharaohs of the ancient Middle East, and they’re different from the challenges faced by traders and maharajas in the pre-modern Indian Ocean. Nonetheless, exploring both of these cases can offer some enduring lessons for making multipolarity work in the 21st century.

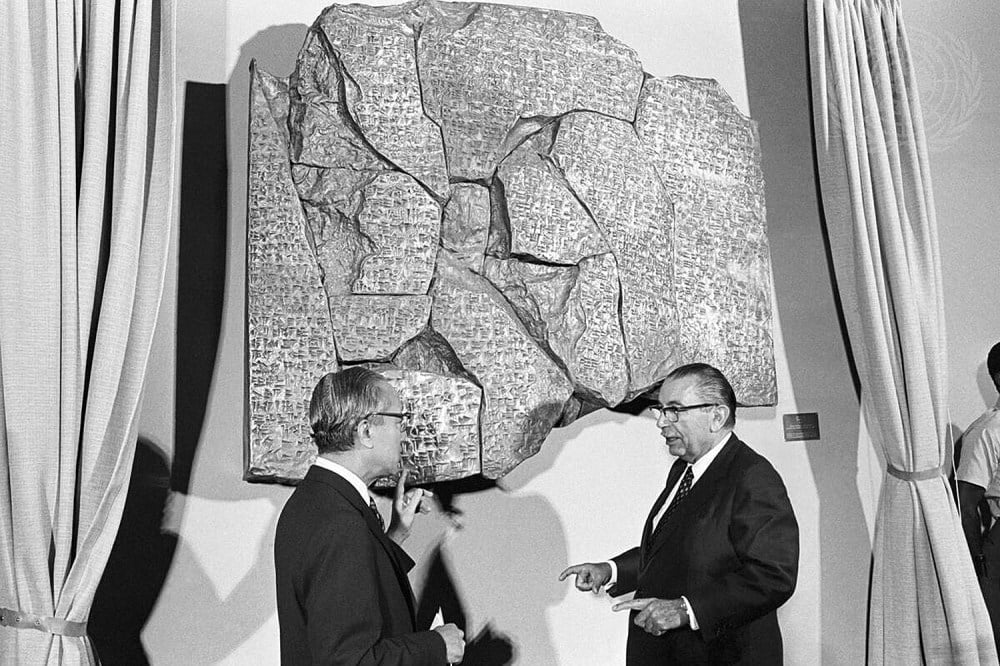

This royal letter from Ashur-uballit, the king of Assyria, to the king of Egypt—circa 1353 to 1336 B.C.—was found in the late 1880s at the site of Amarna, the religious capital of Egypt under Akhenaten. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Around the middle of the second millennium B.C., the heart of the Middle East was ruled by a number of empires: Egypt, Hatti, Mitanni, Assyria, and Babylon. Egypt, as the oldest, wealthiest, and most centralized polity, held the highest status, but it was by no means a hegemon. To the North was Hatti (the empire of the Hittites), an Anatolian power that stretched into the Levant. Next, along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers toward the southeast, was the decentralized empire of Mitanni, followed by Assyria, and then Kassite Babylonia. These five powers comprised an essentially multipolar system, yet they created a stable set of relationships based on the norms of equality and reciprocity.

The principle evidence for how this system worked comes from a cache of 350 letters discovered in 1887 at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt. Although the system they reflect began earlier, these letters date from between 1360-1332 B.C. They were written in Akkadian cuneiform, the lingua franca of ancient Mesopotamia, and preserved in the palace of Pharaoh Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV).

Political scientists who have studied these documents argue that they offer a clear window to “the first international system known to us.” According to Raymond Cohen and Raymond Westbrook, they show “the Great Powers of the entire Near East, from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, interacting among themselves, engaged in regular dynastic, commercial, and strategic relations.” These interactions, Cohen and Westbrook argue, created “a diplomatic regime consisting of rules, conventions, procedures, and institutions governing the representation of and the communication and negotiation between Great Kings.”

A number of empires ruled the heart of the Middle East in the middle of the second millennium B.C. Amitav Acharya map

Diplomatic exchanges show how this regime combined both persuasion and pressure. Highly symbolic language—appealing to a fellow ruler as brother, for example—masked more pragmatic political calculations. Visits, gift-giving, and cultural deference all served to maintain steady communication, gather intelligence, and convey each king’s commitment to their own sovereignty.

In this correspondence can be found all the elements associated with later international orders. Throughout their interactions, the great kings were constantly striving for equal status. One letter, now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, shows Assyria, as a newly rising power, seeking to join the brotherhood of existing powers. Its king, Ashur-uballit, sent a letter to the pharaoh of Egypt, most likely Akhenaten, that simultaneously bestowed gifts upon him while also demanding a quick response and seeking information about Egypt and its ruler. Another letter, from King Burna-Buriash of Babylon to the Egyptian pharaoh, shows the importance of reciprocity. Since the pharaoh had not sent a gift, the king of Babylon was not going to send one either: “Now, although both you and I are friends, three times have your messengers come here but you did not send me one beautiful gift and therefore I did not send you one single beautiful gift.”

This correspondence was embedded in a system that provided for diplomatic immunity and continuous contact, using official stamps and formal ratification by rulers acting in “the presence of divine witnesses.” There was also a notion of sovereign equality. Although nominally enjoying somewhat higher status, the pharaoh of Egypt was also expected to treat all other great kings as equals by giving each of them gifts of similar value. Hence, when Ashur-uballit of Assyria got less gold from Egypt than the king of Mittani, he complained, adding that the gold he received was “not enough for the pay of my messengers on the journey to and back.”

One result of the diplomatic relationship between the great kings of the Middle East was the world’s first peace treaty between Egypt and Hatti. Concluded in 1259 B.C. between Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II and Hittite King Hattusili III, the treaty, written in both Egyptian and Akkadian, contained a number of provisions to manage conflicts between the two powerful states.

A clay tablet with the Kadesh Peace Treaty, signed between the Egyptians and the Hittites, displayed in the Istanbul Archaeological Museums. DeAgostini/Getty Images

One provision enshrined the principle of mutual non-aggression: “The Great Prince of Hatti shall not trespass against the land of Egypt forever, to take anything from it. And … the great ruler of Egypt, shall not trespass against the land of Hatti, to take from it forever.” Another articulated the principle of collective security: “If another enemy come against the lands of … Egypt, and he send to the Great Prince of Hatti, saying: ‘Come with me as reinforcement against him,’ the Great Prince of Hatti shall come to him and … slay his enemy.” Similarly, “if another enemy come against the Great Prince of Hatti, … the great ruler of Egypt, shall come to him as reinforcement to slay his enemy.” There is even a provision providing for extradition: “If a great man flee from the land of Egypt and come to … Hatti … the Great Prince of Hatti shall not receive them (but) … cause them to be brought to … the great ruler of Egypt.”

Taken together, these letters challenge the influential view that great-power rivalries lead to catastrophic wars. To be sure, the ancient Middle East was not without tensions, and the individual powers still waged military campaigns against their smaller neighbors. But they avoided fighting each other. According to Cohen and Westbrook, the five empires “negotiated rather than fought” and, “with rare exceptions,” “succeeded in accommodating each other’s needs and ambitions.”

Of course, multipolar systems are not inherently stable either. The Amarna correspondence also demonstrates the conditions under which such a system can function peacefully. Maintaining regular communications and respecting norms of reciprocity are both vital for effective diplomacy.

Despite its significance, one hears little about the ancient Middle East order as opposed to the European concert of powers, a similar system that emerged 2,300 years later following Napoleon’s defeat. The Concert of Europe, which Henry Kissinger, among others, extolled, lasted, with interruptions, for the better part of a century. Its Middle Eastern precursor, with a greater dose of mutual respect and reciprocity, lasted at least twice as long, arguably maintaining stability for roughly 200 years.

A code of laws of the Malay kingdom of Malacca, an early 19th-century manuscript with the Acehnese variant of the text.British Library

Closely related to the fear of multipolarity is the widely held assumption that stability and prosperity require a single dominant power. But history also provides alternative models for preserving free trade in a multipolar system. The best example of this comes from the Indian Ocean. For centuries before the arrival of European colonial powers, the Indian Ocean was the world’s largest open oceanic trading system. Trade in the Indian Ocean was managed by a string of city states stretching from Malindi and Mombasa in East Africa to Hormuz and Aden in West Asia and Calicut, Malacca, and Makassar in today’s South and Southeast Asia.

We know a fair amount about how this trading network operated because of a legal code called the Undang-Undang Laut Melaka (Maritime Laws of Malacca). Drafted in the 15th century by a group of sea captains, it provided rules for a host of common maritime issues. The code specified the authority of a trading ship’s captain and the responsibilities of the crew, as well as a method for settling contractual obligations and debts incurred at sea. It also established regulations on profit-sharing, compensation for collision damage, and penalties for cheating on port duties.

Malacca itself was not a great power. But as a port city, it established a trading system that was free, fair, and transparent. In the 15th century, Malacca had a population of about 100,000, mostly foreign traders, who spoke more than 80 languages. Trade was open to all nationalities and subject to a well-established customs duty of 4 to 6 percent. Trading was far from chaotic. Instead, it was “well regulated”—or “rules-based,” to use a more contemporary term. Local rulers did not interfere with foreign merchants; prices were set and disputes settled by representatives of foreign trading communities: Arabs, Indians, Chinese, and Javanese. Malacca had a system whereby the captain or owner of a ship could sell his cargo at a single price upon arrival to a group of 10 or 20 local merchants, who would then distribute the cargo among them. This system let ships clear their cargo quickly without the need to find individual buyers, something particularly important when they had to follow precise sailing times in accordance with monsoon winds. It also meant that the range of prices foreign goods would fetch in Malacca was predictable.

The Indian Ocean trade network. Amitav Acharya map

Crucially, this trading system did not depend on the hegemony of any regional power. Despite the desire of some modern historians to suggest otherwise, the Indian Ocean was never a Chinese sphere of influence. Although many Southeast Asian states—including Srivijaya, Malacca, and Siam—had tributary relations with China, the trade was neither dominated nor managed by China. And although the Chinese deployed a large fleet under Adm. Zheng He seven times during the early 15th century, their goal in doing so was never to build an empire in the Indian Ocean.

Similarly, India had a strong cultural and economic role in the Indian Ocean, but this did not imply strategic dominance. There are only two recorded naval expeditions from India—both from the southern Indian Chola kingdom, and both in the 11th century. These expeditions spread destruction but did not create a Chola empire with hegemony over the Indian Ocean. Even the mighty Moghul Empire stayed out of the business of controlling the oceans. While powers like Venice sought to expand their boundaries over the maritime domain, the Moghuls deferred to a regional tradition that prohibited this. Unlike the Mediterranean, where the sea was parceled out, or in the Hanseatic League of Europe, where the right of free trade was open only to the members of the league, Indian Ocean trade was open to all nationalities.

Where cities like Malacca pioneered this open and rules-based system, Western writers often credit the Dutch legal scholar Hugo Grotius with the idea of the freedom of the seas. Yet Grotius wrote his seminal work, Mare Liberum, on the payroll of the Dutch East India Company. It was part of a commissioned legal treatise to defend the Dutch seizure of a Portuguese vessel returning from the East Indies—carried out, as it happens, by Grotius’s cousin. As the first European power to arrive in the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese had established a monopoly over it, denying not only Asian kingdoms, but also rival European powers, equal trading access. Grotius argued his cousin had struck a blow against Portuguese monopoly in support of the Dutch right to free trade. But inevitably, after defeating the Portuguese, the Dutch East India Company went on to establish a monopoly of its own over the vast archipelago now known as Indonesia. In time, Grotius’s employer would destroy the region’s rules-based regime, forcing local rulers to stop trading among themselves and trade only through the Dutch.

In the early 17th century, the Dutch barred merchants from the Gowan city of Makassar (in South Sulawesi) from purchasing cloves, nutmeg, and mace in the Maluku Islands. Faced with this infringement on free trade, Sultan Alauddin, Gowa’s ruler, declared: “God made the land and the sea; the land he divided among men and the sea he gave in common. It has never been heard that anyone should be forbidden to sails the seas.” In response to this assertation of principle, the Dutch increased their coercion, then finally seized and destroyed Makassar’s main military stronghold, rebuilding it as Fort Rotterdam.

The two examples discussed here—the multipower system of the ancient Middle East and the small-power managed trading network of the Indian Ocean—show how different multipolarity looks from a broader historical perspective. The dominance of a single nation was not always a prerequisite for peace or free trade. Policymakers and analysts need not accept history that make timeless and universal claims based on few centuries or places. The experience of Europe before World War II will not necessarily replicate itself in the 21st century.